What Is Paleolithic Art Jean Clottes University of Alabama

Geographical Region

Obviously, rock fine art locations heavily depend upon the presence (or absence) of caves and shelters. However, areas which ane might accept thought favourable on that business relationship, such as Languedoc, Roussillon, Provence or again the valleys and causses in the south of Quercy and Aveyron have few or no painted or engraved sites. Cultural choices were a determining factor. Differential preservation is another one, as many caves and shelters may have been destroyed by all sorts of phenomena. For instance, at the terminate of the terminal glaciation, the 115 meters rise of the bounding main flooded dozens of caves in the Mediterranean. Several could have had wall art. Simply one was partly preserved (Cosquer).

Four primary areas with Paleolithic (or Palaeolithic or Palæolithic) rock art stand out. The most important one is that of Perigord, with more than sixty sites, ranging over the twenty thousand years during which wall art was done and including some of the almost spectacular caves e'er discovered for paintings (Lascaux, Rouffignac, Font-de-Gaume), engravings (Les Combarelles, Cussac) or low-relief sculpture (Le Cap Blanc).

Quercy (particularly the Lot merely also the Tarn and Tarn-et-Garonne) is a group in itself, immediately e and south of that of Dordogne. It includes more than thirty painted caves.

The major ones are Cougnac and Pech-Merle. The Pyrenees constitute a grouping equivalent to that of Quercy. Its thirty-odd painted or engraved caves are mostly Magdalenian, but a few are older (Gargas, some galleries in Les Trois-Freres and Portel). They are often to be establish in pocket-size groupings, like the Basque caves in the Arbailles mountains in the westward of the concatenation, the three Volp Caves, and the six caverns in the Tarascon-sur-Ariege Basin. Several are virtually important (Niaux, Les Trois-Freres, Le Tuc d'Audoubert, Le Portel, Gargas).

The lower valley of the Ardeche used to be considered equally a minor group - numbering virtually 20 caves - before the discovery of the Chauvet Cave, in itself a most exceptional site. The other caves and shelters with rock fine art are scattered in diverse places : the Cosquer Cave Provence by the Mediterranean, Pair-non-Pair in the Gironde, Le Placard, La Chaire-a-Calvin, Roc-de-Sers in the Charente, Le Roc-aux- Sorciers and its splendid sculptures in the Vienne, the two caves of Arcy-sur-Cure in Burgundy, the Mayenne Sciences cave in the Mayenne, one or two shelters in the Fontainebleau Forest and two other caves, including Gouy, in Normandy.

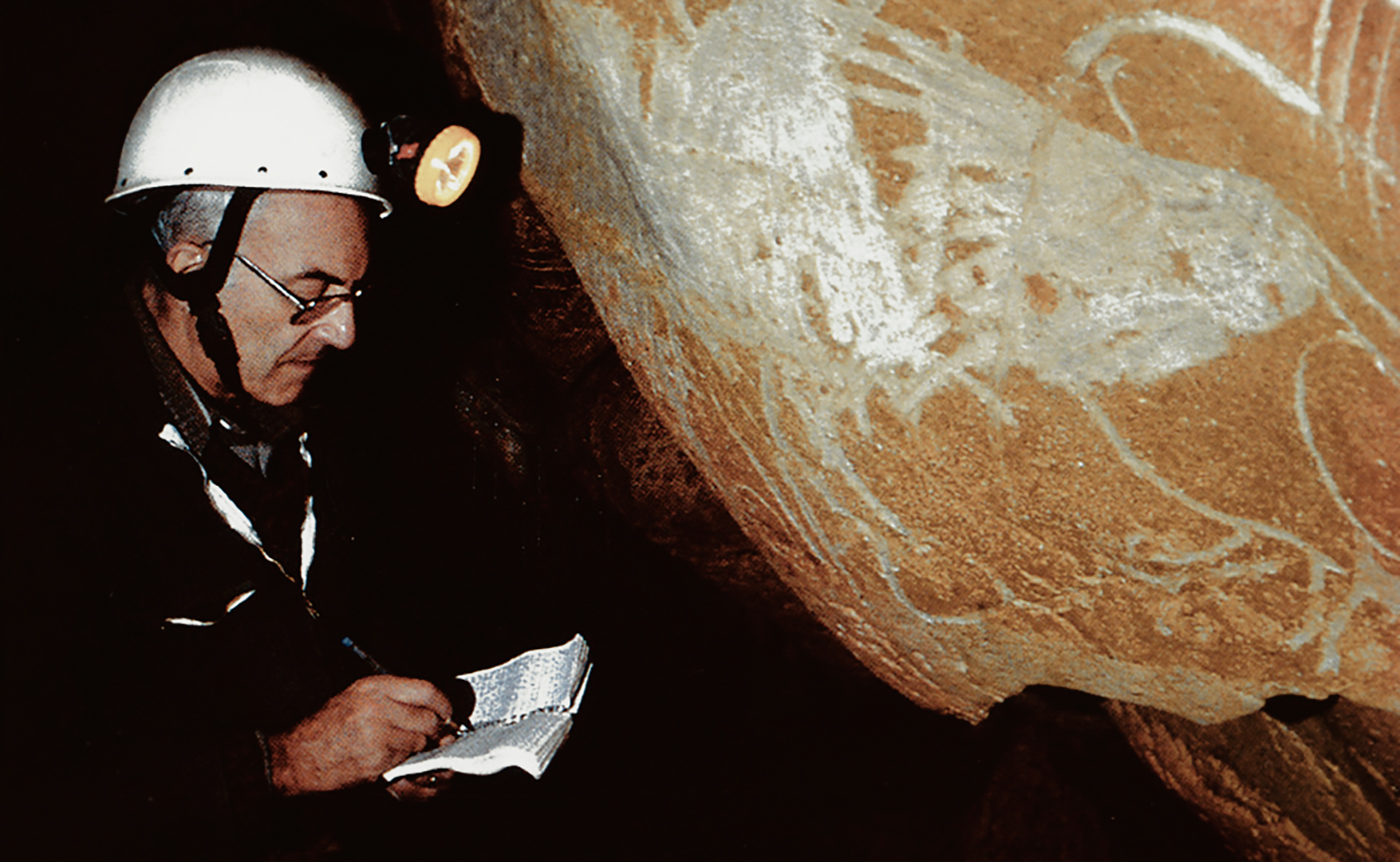

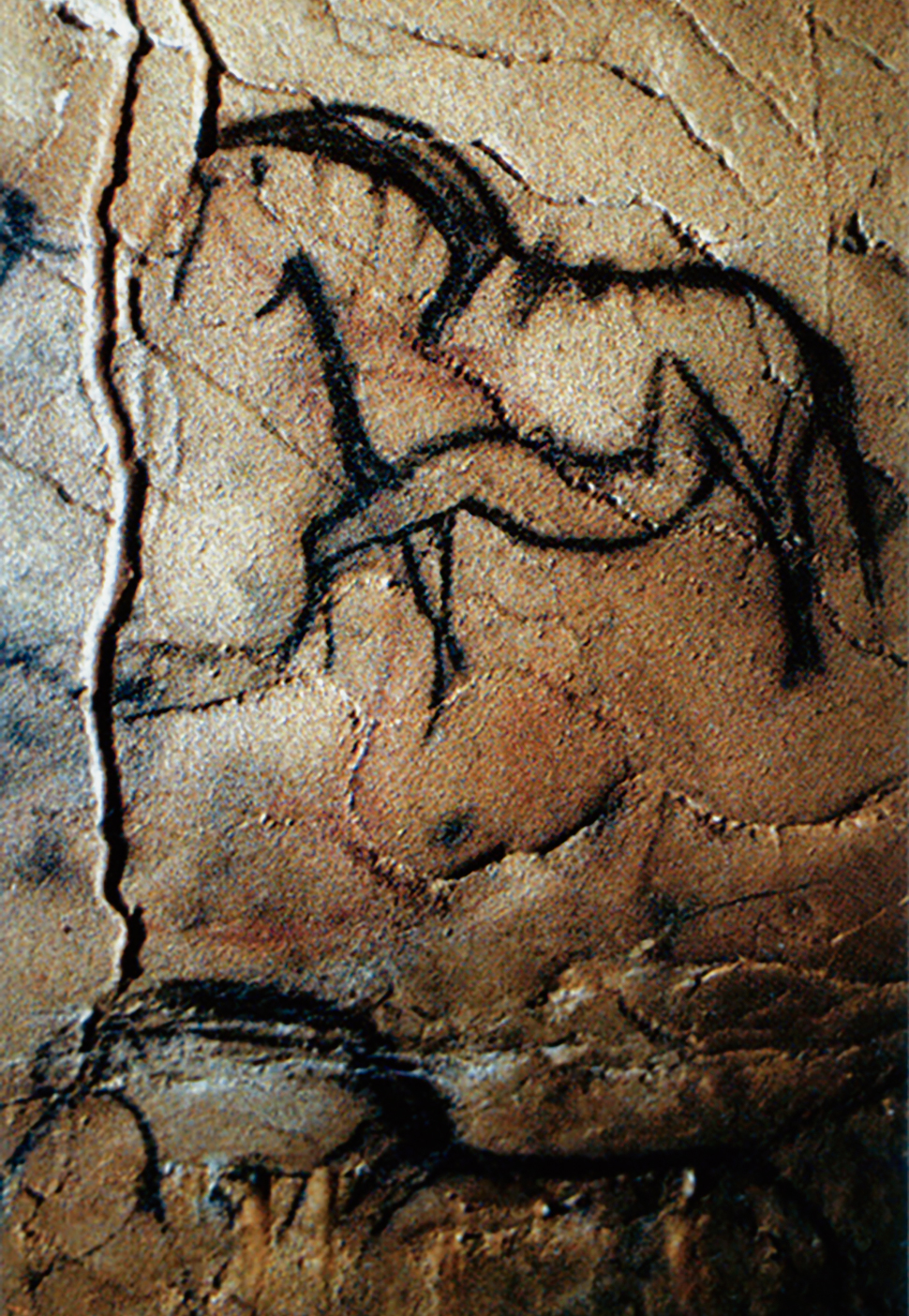

Keen Blackness Balderdash from the Lascaux Cave

© North. Aujoulat (2003) © MCC-CNP

Opposite to a well-spread thought, Paleolithic stone art is non merely a 'cave fine art'. In fact, a recent study showed that if the fine art of 88 sites was to be found in the complete nighttime, in 65 other cases it was in the daylight (Clottes 1997). Three master cases tin be distinguished : - the deep caves, for which an bogus light was necessary; - the shelters which were more or less lit up past natural calorie-free ; - the open air sites. The latter are substantially known in Spain and Portugal. Simply one instance has been discovered in France (the engraved rock at Campome in the Pyrenees-Orientales). The art in the light and the art in the dark: those two tendencies take coexisted for all the elapsing of the Paleolithic. The art in the dark was preferred in sure areas (the Pyrenees) and at certain periods (Middle and Tardily Magdalenian). The low-relief sculptures are but to be constitute in shelters. On the other hand, the paintings which used to be in shelters have for the most part eroded abroad and only very faint traces remain, contrary to engravings which could in many cases be preserved in them.

In the shelters, there have about ofttimes been settlements adjacent to the wall art. People lived there and went on with their daily pursuits close to the engravings, the paintings and depression-relief sculptures. The instance is quite unlike for the deep caves which ordinarily remained uninhabited. This must hateful that the art of the one and that of the other were probably not considered in the same way: in the deep caves the images were nigh never defaced, destroyed or erased, where as in the shelters the archaeological layers - i.eastward. the rubbish thrown away by the group - ofttimes ended upward by covering upward the art on the walls (Gourdan, Le Placard). The art inside the caves was respected, while the art in the shelters eventually lost its interest and protection.

The Themes Chosen

Whether for the fine art in the nighttime or for the art in the calorie-free, the themes represented are the same. They evidence to identical beliefs, even if ritual practices may have varied co-ordinate to the different locations.

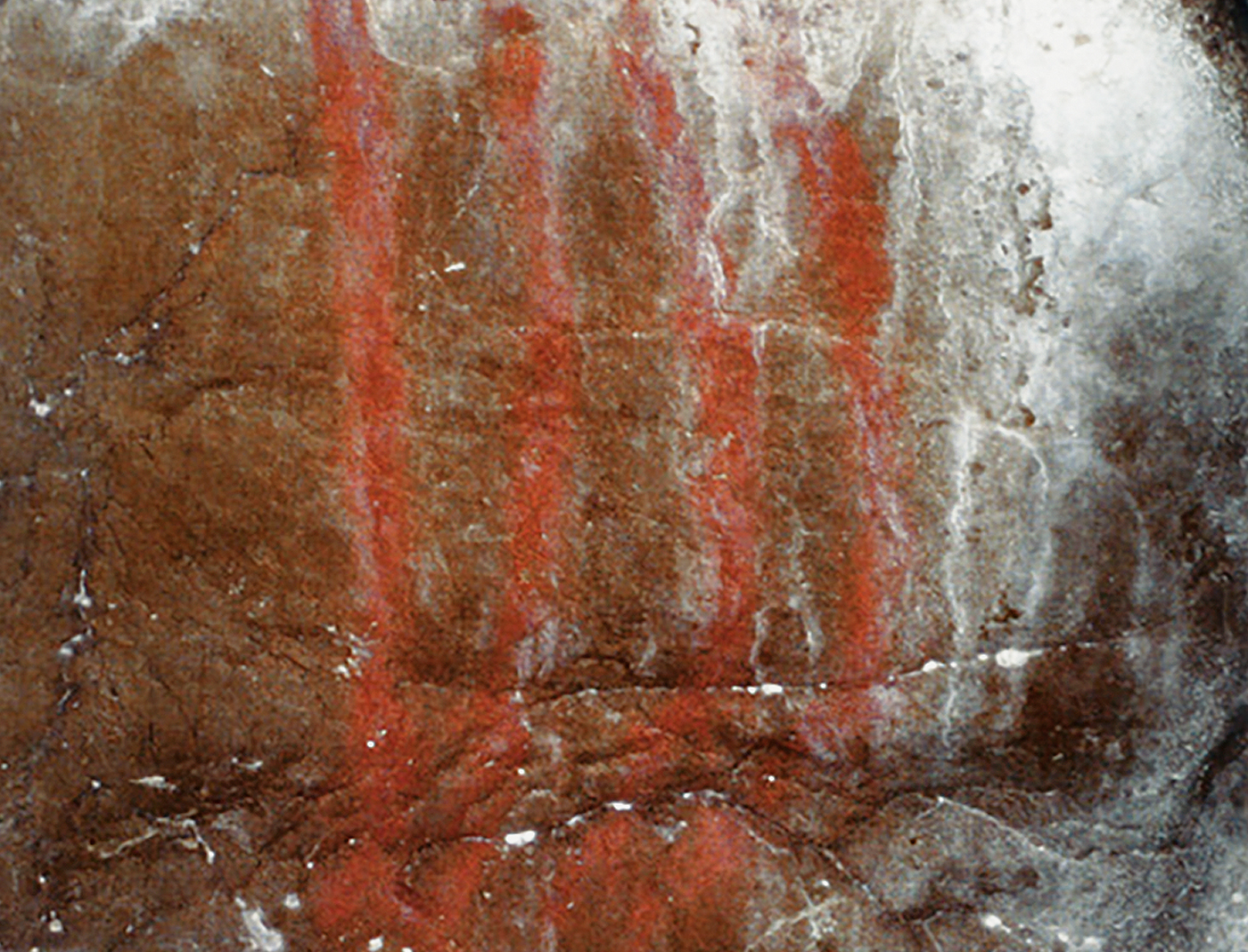

Above all, Paleolithic art, from beginning to end, is an art of animals. In the by few years, some specialists have insisted upon the importance of geometric signs. It is true that those signs and indeterminate traces are numerically more of import than the animals and that they constitute one of the major characteristics of the fine art. Under their most elementary forms, every bit clouds of dots and minor cherry confined, they tin be establish from the Aurignacian in Chauvet to the Middle and Tardily Magdalenian in Niaux. They are the about mysterious images in cave art. Very few caves accept none (Mayriere superieure, La Magdelaine) or, on the opposite, have nothing but geometric signs (Cantal and Frayssinet-le- Gelat in the Lot). This means that those signs are practically e'er associated to animals, either in the same caves and often on the same panels or directly on top of them (G.R.A.P.P. 1993).

Serial of cherry-red dots

constitute in the Niaux Cave

Red bars painted near

entrance of Niaux Cavern

Red hand stencil from

the Chauvet Cave

Hand stencils and prints can exclusively

be found in the earliest periods of the art

Reclining woman, La Magdelaine des

Albis Cave, Penne, Tarn, France

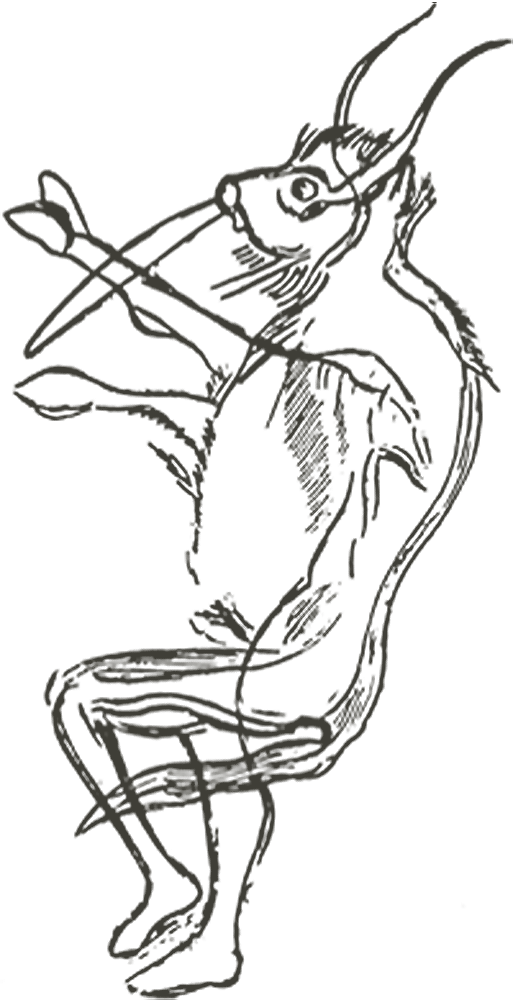

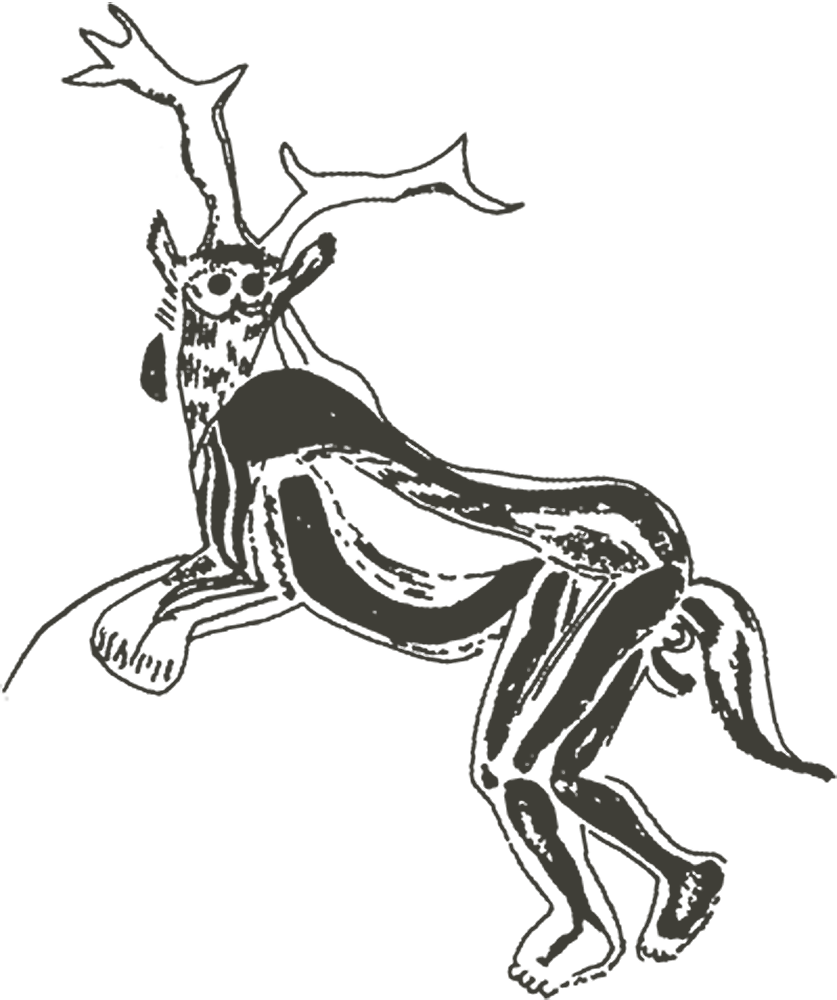

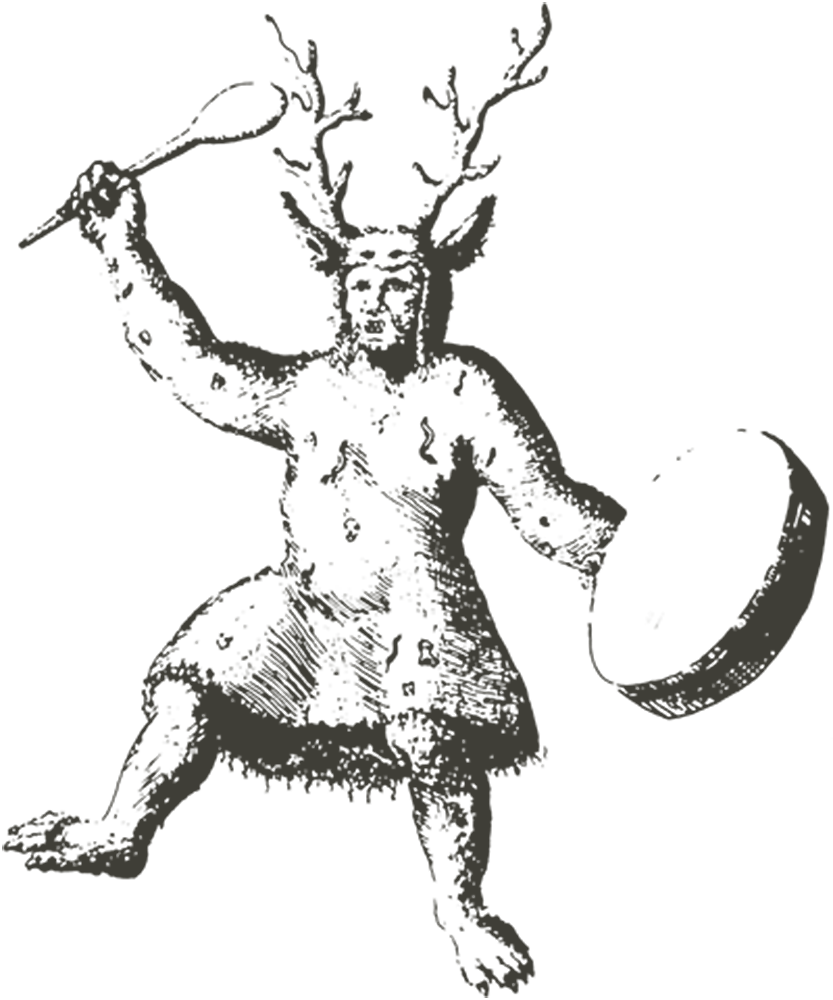

Wizard from

the Chauvet Cavern

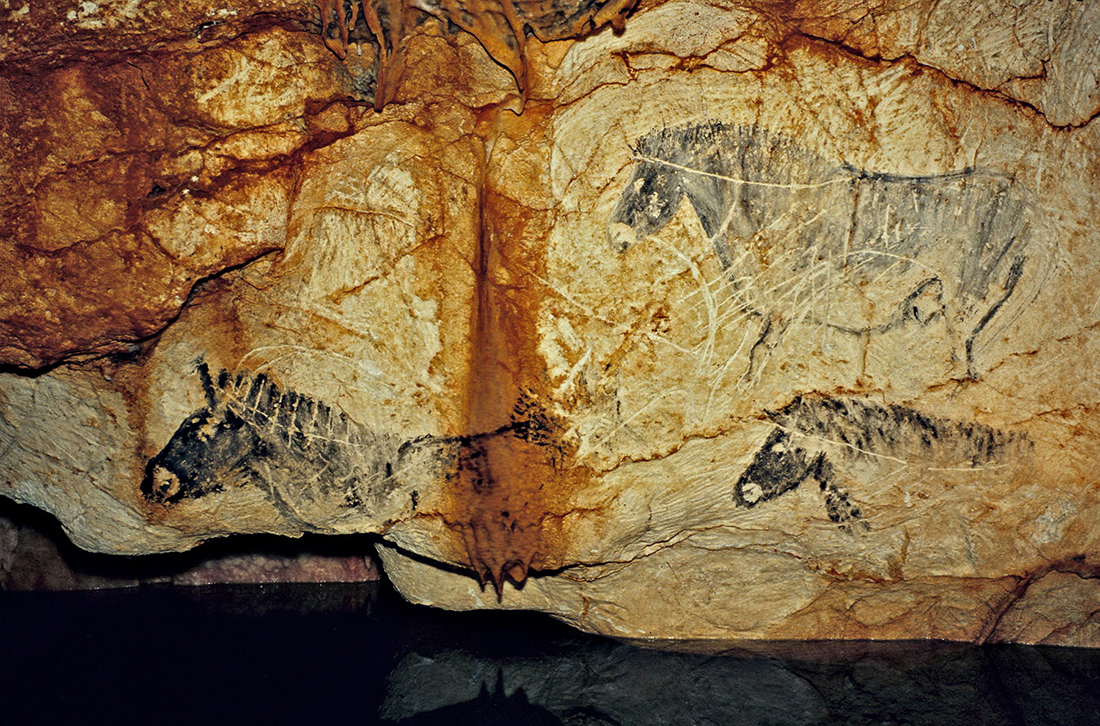

Horses in the Cave of Le Portel

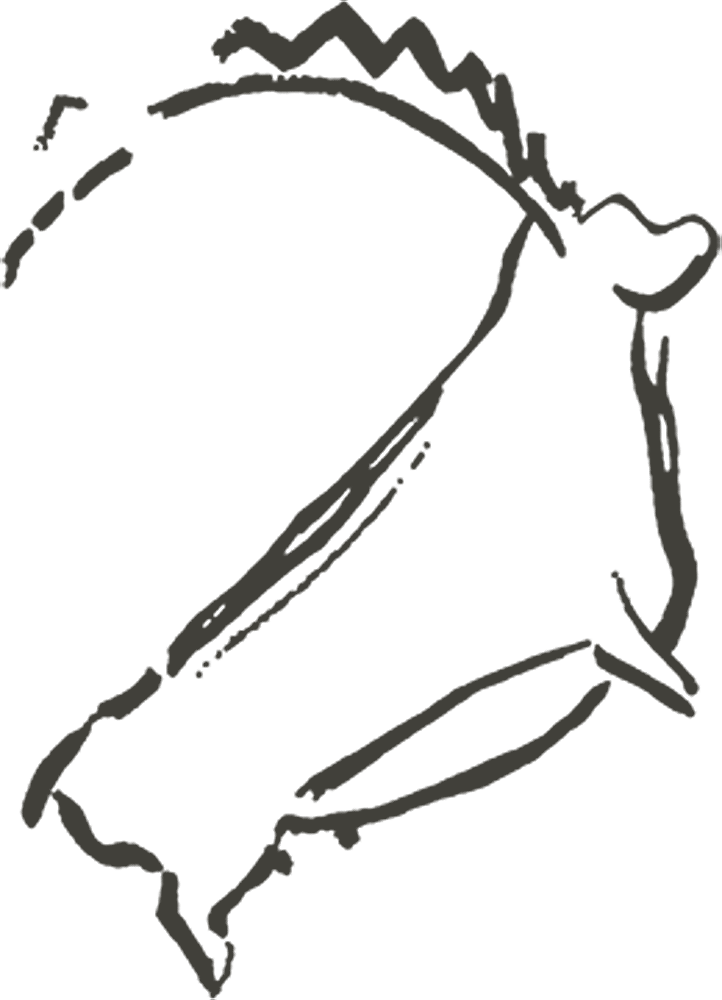

Still, our first and most durable impression of Paleolithic art is above all that of a bestiary, plentiful and various while remaining typical. Most of the animals represented are large herbivores, those that the people of the Upper Paleolithic could see around them and which they hunted. Those choices were not compulsory. They might have preferred to draw birds, fish or snakes, but they did not do and then.

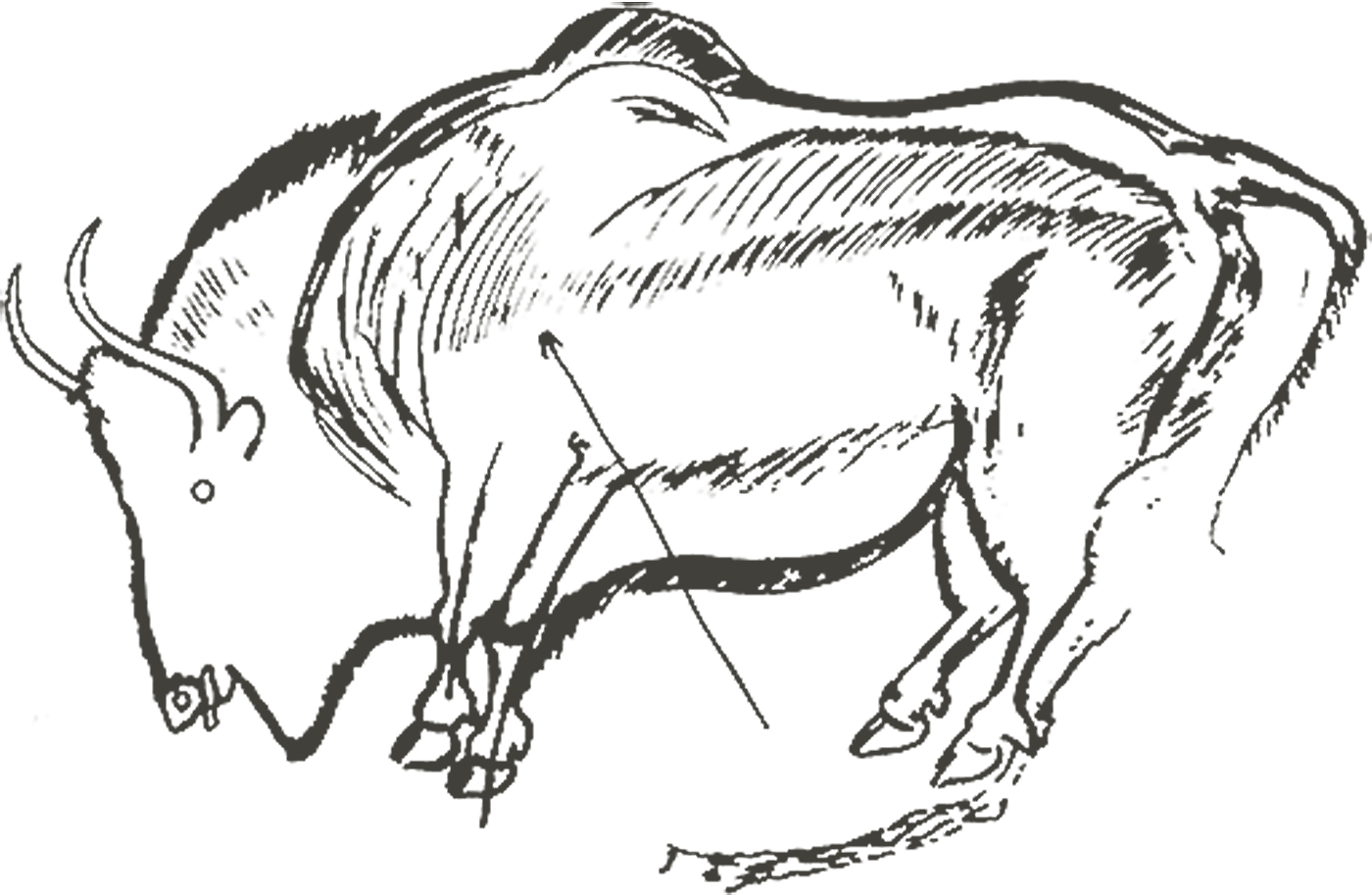

Horses are ascendant. Locally they may be outnumbered past bison (the Ariege Pyrenees;) or hinds (Cantabrian Spain), occasionally even by rhinoceroses and lions at the very starting time (Chauvet) or, much later, by mammoths at Rouffignac (Plassard 1999). None the less, they ever remain numerous whatsoever techniques were used at any period and in whatever region. We might say that the theme of the horse is at the basis of Paleolithic rock art. This is all the more remarkable as that animal, even though nowadays amongst the cooking debris of Paleolithic living sites, was often less plentifully killed and eaten than reindeer and bison, or again ibex in mountainous rocky areas. This means that it played a major role in the bestiary. The aforementioned could be said, even if less so, for the bison, whose images are likewise constitute in relatively high numbers from the Aurignacian to the end of the Magdalenian.

The importance of fauna themes varies according to the different regions merely much more in role of the periods considered. For ex-ample, the enormous number of usually rare dangerous animals in the Chauvet Cave created a surprise: rhinoceroses, lions, mammoths and bears represent 63% of the recognisable animal figures (Clottes (ed.) 2001).

However, this is not a unique phenomenon, isolated in time and space. In the Dordogne, at the aforementioned epoch, Aurignacians fabricated use of the same themes in their shelters and their caves in much higher proportions than can exist found in later art. This would mean that an important thematic change took place in the fine art of the south of France at the beginning of the Gravettian or at the cease of the Aurignacian, when their choices changed from the most fearsome animals to the more hunted ones (Clottes 1996). Human representations tin be institute, merely in far fewer numbers in comparison with the painted and engraved animals. Most a hundred have been published, not counting mitt stencils and hand prints or isolated female sexual organs. This numerical inferiority, constant at all times during the Upper Paleolithic, is in sharp contrast to what one tin can see in most forms of rock art all over the world. In addition to their relative scarcity, human representations prove ii main characteristics: they are nearly always incomplete or fifty-fifty reduced to an isolated segment of their body; they are not naturalistic, contrary to the animals.

Whole man representations are exceptional, hardly a score. They may be carved women (La Magdelaine in the Tarn, Le Roc aux Sorciers in the Vienne), or women sketched with a finger or a tool on the soft surface of a wall or ceiling (Pech-Merle, Cussac), or painted (Le Portel) or engraved men (Sous-Thousand-Lac, Saint-Cirq, Gabillou in the Dordogne).

Far more numerous are body segments, such as mitt stencils and hand prints, heads, female person and male genital organs, or once more some rather indistinct outlines - which may or may not be human - often chosen 'ghosts'. Those themes were more or less favoured co-ordinate to the various cultures (Thousand.R.A.P.P. 1993). Mitt stencils and prints can exclusively be establish in the primeval periods of the fine art, probably in the Aurignacian (Chauvet), most certainly in the Gravettian (Cosquer, Pech-Merle, Gargas), roughly between 32,000 and 22,000 BP in uncalibrated radiocarbon years. On the other hand, the female sexes, frequent at the very starting time (Chauvet, Cosquer, several shelters in Dordogne), can also be found in the Solutrean and above all in the Magdalenian (Font-Bargeix, Bedeilhac). That sexual theme is thus a abiding of the Upper Paleolithic, with more or less frequent occurrences according to the times and places.

Animals are often drawn without any care for scale, in profile. They tin can exist whole or just represented by their heads or forequarters, which is plenty to identify them. Their images are often precise, personalised and identifiable in all their details (sexes, ages, attitudes), whether they exist Magdalenian bison in the Ariege or Aurignacian lions and rhinos in the Chauvet Cave, xviii,000 years earlier. Scenes are rare and certain themes are absent, like herds and mating scenes. Paintings and engravings are thus neither faithful copies of the surrounding environment nor stereotypes.

As to humans, whatever the culture and various as they may be, they ever seem to be uncouth and unsophisticated, mere caricatures. This is as well a constant feature that stresses the unity of Paleolithic art.

The artistic abilities of the painters and engravers cannot be questioned. They deliberately chose to represent vague humans, with few details or deformed features.

A particular theme is that of composite creatures, at times called sorcerers. Those beings evidence both human being and fauna characteristics. This theme is all the more interesting equally it departs from normality. Information technology is present as early as the Aurignacian in Chauvet. It can be found in Gabillou and Lascaux 10,000 years later or more and it is still present in the Middle Magdalenian of Les Trois-Freres, nearly twenty,000 years afterwards its ancestry.

The Techniques Utilised

Le Cap Blanc Horse Sculptures

In France, only xviii sites are known with sculptures. The most important ones are Le Cap Blanc in the Dordogne and the Roc-aux-Sorciers in the Vienne (lakovieva & Pinion 1997, Airvaux 2001). That technique is the one that required about piece of work. Some images evidence a 5 cm relief or more. It is present in all the master groups except that of the south-eastward.

Clay modellings are all dated to the Middle or Late Magdalenian and they are all establish within a restricted surface area, in four caves of the Ariege Pyrenees : Labouiche, Bedeilhac, Montespan and Le Tuc d'Audoubert. Those in the latter two caves are famous, Montespan considering of a clay bear which is a real statue, nearly lifesize, and Le Tuc d'Audoubert because of two boggling bison following each other in a premating scene. A especially naturalistic female person figure was modelled on the basis in Bedeilhac. Information technology is difficult to understand why other works made with such a uncomplicated technique accept not been found in other groups and at other periods.

Finger tracings from the Rouffignac Cavern

Finger tracings are everywhere. Their presence depends upon the qualities of the walls : when their surface is soft it becomes possible to depict with one's fingers. Finger tracings are often not naturalistic, with volutes and incomprehensible squiggles that occupy many square meters on the walls and ceilings, as in Gargas and Cosquer (Clottes & Courtin 1996). Most ofttimes they belong to the earliest periods of the fine art. The engravings on the footing are more frequent in the Pyrenees than anywhere else. For them as for the paintings in the open preservation problems are vital: it is so easy not to notice them and to destroy them by trampling. This must accept happened innumerable times.

The engravings on the walls are less famous than the paintings considering they are less spectacular, but they probably are more numerous. They were generally made with a flint and the effects accomplished are very diverse. Sometimes, the artists contented themselves with sketching the outlines of animals by means of simple lines which can be deep and wide or thin and superficial according to the hardness of the surface. The finest ones can only exist seen now under a slanting lite, but modern experimentation has shown that they must have been far more visible at the time they were fabricated, when they stood out white against the darker color of the wall; since then they have go patinated and their colour is the aforementioned every bit that of their environment. This remark may explicate the very numerous superimpositions of motifs that tin be establish in caves like Les Trois-Freres, Lascaux or Les Combarelles. In other cases, the artists used scraping, which shows white on the wall and enables all sorts of possibilities by playing with the darker hues of the wall and the lighter ones of engravings (Les Trois-Freres, Labastide) (M.R.A.P.P. 1993).

Paintings are generally red or black. The reds are iron oxides, such as hematite. The blacks, either charcoal or manganese dioxide. Sometimes they did real drawings with a chunk of stone or of charcoal held like a pencil. Elsewhere veritable paintings were made. The pigment was then crushed and mixed with a binder to ensure the fluidity of the paint which was then either applied with a finger or with a brush fabricated with brute hair, or diddled through the oral fissure (stencilling).

Modern analyses even revealed that in the Magdalenian of the Pyrenees some paintings (Niaux, Fontanet) had been made according to real recipes by adding an extender, i.e. a powder obtained from the crushing of various stones (biotite, potassium feldspath, talcum). The aims were to salvage on the pigment, to make the paint stick ameliorate to the wall and to avert its crackling when drying (Clottes, Card, Walter 1990). Some images evince dissimilar techniques for the same discipline : bicolour, joint utilize of engraving & painting.

Equally early as the Aurignacian, more than 30,000 years agone, the nigh sophisticated techniques of representation had been discovered and were in use, as can be seen in the Chauvet Cavern. Those artists made use of stump drawing in order to shade the within of the bodies and provide relief. They too used the main two colours (red and black), fine and deep engraving, finger tracing and stencilling.

Chronology

Visitors to the Niaux Cave in Franc in the early 20th century

Until the end of the eighties, it was impossible to date paintings directly, every bit the quantity of pigment necessary for such an analysis was as well excessive. Accelerator mass spectrometry at present enables united states of america to obtain a date with less than ane milligram of charcoal. Consequently, a number of directly dates are now available for half-dozen French caves : Cosquer, Chauvet, Cougnac, Pech-Merle, Niaux, Le Portel. When the caves accept simply got engravings (Les Combarelles, Cussac) or ruddy paintings, or blackness paintings made with manganese dioxide (Lascaux, Rouffignac), it remains impossible to get a straight date because of the lack of organic material. Chronological attributions are then fabricated with time-honoured methods, by and large by taking advantage of the archaeological context whenever possible or from stylistic comparison with other better dated sites. For example, when the Cussac cave was discovered in the Dordogne in October 2000, Norbert Aujoulat and Christian Archambeau attributed its engravings to the Gravettian considering of the similarities with Pech-Merle and Gargas (Aujoulat et al. 2001). When, in Baronial 2001, a 25,120 BP ± 120 date was obtained from a homo bone in the same cavern, it corroborated the initial judge of those specialists (op. cit.).

| Chronology of Paleolithic Cavern Art in France | |||

| Parietal Site | Prototype | Age BP | Culture |

| Le Portel | | 11.600 ± 150 BP | Magdalenian |

| Trois-Freres | | 13.000 ± BP | |

| Rouffignac | | 13.000 ± BP | |

| Niaux | | 14.000 ± eleven.500 BP | |

| Le Cap Blanc | | 15.000 ± 14.000 BP | |

| Altamira | | 17.000 ± 13.000 BP | |

| Cosquer (Phase 2) | | 19.000 ± BP | Solutrean |

| Lascaux | | 20.000 ± BP | |

| Le Placard | | 21.000 ± twenty.000 BP | |

| Cougnac | | 25.000 ± xiv.000 BP | Gravettian |

| Pech-Merle | | 25.000 ± 16.000 BP | |

| Gargas | | 27.000 ± BP | |

| Cosquer | | 27.000 ± BP | |

| Chauvet | | 32.000 ± 30.000 BP | Aurignacian |

Luc Vanrell, Jean Courtin & Jean Clottes examining engravings in the Cosquer Cave

Among well-established facts, the most important is the duration of cave art, over at least 20 millenia. The oldest dates are so far those of the Chauvet Cave (between 30,000 and 32,000 BP) and the most recent ane that in Le Portel (11.600 ± 150 BP).

Such an immense duration implies several consequences. Outset, the acknowledgement that in order for such a tradition to persist under such a formalised form for such a long time, information technology must have meant that a strong compelling form of teaching existed. The fundamental unity of Paleolithic art, obvious every bit it is in its images and in the activities around it, could not but for that have persisted for so many millenia. It is as well a fact that the apparent slap-up number of painted or engraved caves and shelters is not much when compared to the duration of Paleolithic art. This means that in that location must have been an art in the open which has not been preserved in France, and also that the images, in hundreds of shelters and caves may have been destroyed or cached and concealed for a number of reasons.

Until a rather recent date, the evolution of fine art was believed to have been gradual, from coarse beginnings in the Aurignacian to the apogee of Lascaux. The contempo discoveries of Cosquer, Chauvet and Cussac have shown that that epitome was wrong, since from every bit early on as the Aurignacian and the Gravettian very sophisticated techniques had already been invented. This ways that forms of art evidencing different degrees of mastery must have coexisted in different places and times and also that many artistic discoveries were made and lost and made again thousands of years later. The evolution of Paleolithic fine art was not in a straight line, but rather as a seesaw.

Homo and Animal Activities in the Deep Caves

Paleolithic wall fine art cannot be dissociated from its archaeological context. This ways the traces and remains of human being and beast activities in the deep caves are valuable clues well-nigh the deportment of their visitors, and are amend preserved in them than in whatever other milieu.

Bears, particularly cavern bears, hibernated in the deepest galleries. Some died and their bones were noticed by Paleolithic people when they went underground. At times they made use of them : they strung them along the way and lifted their impressive canines in Le Tuc d'Audoubert; in Chauvet, they deposited a skull on a big rock in the middle of a bedchamber and stuck 2 humerus forcibly into the ground non far from the entrance. Cavern bears scratched the walls as bears do trees and their very noticeable scratchings may have spurred people to make finger tracings (Chauvet) or engravings (Le Portel).

Humans left various sorts of traces, whether deliberately or involuntarily. When the ground was soft (sand, moisture dirt), their naked footprints remained printed in information technology. (Niaux, Le Reseau Clastres, Le Tuc d'Audoubert, Montespan, Lalbastide, Fontanet, Pech-Merle, Fifty'Aldlene, Chauvet). This enables us to see that children, at times very young ones, accompanied adults when they went hole-and-corner, and also that the visitors of those deep caves were not very numerous considering footprints and more by and large human traces and remains, are few.

Human being skeletons in Cussac Cave

The charcoal fallen from their torches, their fires, a few objects, bones and flintstone tools left on the basis are the remains of meals or of sundry activities. They are too part of the documentation unwiittingly left by prehistoric people in the caves. From their study, one can say that in most cases painted or engraved caves were not inhabited, at least for long periods. Fires were temporary and remains are relatively scarce. Naturally, there are exceptions (Einlene, Labastide, Le Mas d'Azil, Bdeilhac). In their case, it is often difficult to make out whether those settlements are in relation - as seems likely - or not with the art on the walls. The presence of portable art may be a valuable inkling to constitute such a human relationship.

Amid the virtually mysterious remains are the objects deposited in the cracks of the walls and in particular the bone fragments stuck forcibly into them (see besides below). After beingness noticed in the Ariegie Volp Caves. (Enlene, Les Trois- Freres, Le Tuc d'Audoubert) (Begouen & Clottes 1981), those deposits have been constitute in numerous other French Paleolithic art caves (Bedeillhaic, Le Portel, Troubat, Erberua, Gargas, etc.). They belong to periods sometimes far autonomously, which is non the least interesting fact near them because this ways that the aforementioned gestures were repeated again and again for many thousands of years. Thus, in Gargas, a bone fragment lifted from one of the fissures next to some hand stencils was dated to 26,800 BP, while in other caves they are Magdalenian i.eastward. more recent by 13,000 to 14,000 years.

The Gravettian burials very recently discovered in the Cussac cavern (Aujoulat et al. 2001) pose a huge problem. It is the first time that homo skeletons have been establish within a deep cave with Paleolithic fine art. Until they accept been excavated and studied properly information technology will exist impossible to know whether those people died there by accident (which is virtually unlikely), whether they were related to those who did the engravings, whether they enjoyed a special status, etc. Their presence just stresses the magic/religious grapheme of art in the deep caves.

Meaning(s)

Ever since the beginning of the 20th century, several attempts take been fabricated to observe the meaning(south) of Paleolithic rock art. Art for art's sake, totemism, the Abbe Breuil'southward hunting magic and Leroi-Gourhan's and Laming-Emperaires'south structuralist theories were proposed and so abandoned one subsequently the other (Delporte 1990, Lorblanchet 1995). Since then, nigh specialists take made up their minds that it would exist hopeless to look for the meanings backside the art. They prefer to spend their time and efforts recording it, describing it and dating it, to endeavor to answer the questions 'what?', 'how?' and 'when?', thus advisedly avoiding the cardinal question 'why?'. In the course of the past few years, though, a new endeavour, spurred past David Lewis-Williams, was made in society to discover an interpretative framework. Shamanism was proposed (Clottes & Lewis-Williams 1998). Because the fact that shamanism is so widespread among hunter-gatherers and that Upper Paleolithic people were admittedly hunter-gatherers, looking to shamanism every bit a probable organized religion for them should accept been the first logical pace whenever the question of meaning arose.

A Bison from the Niaux cave follows the natural ridge of the cave wall

In addition, shamanic religions evidence several characteristics which tin can make u.s. understand cave art ameliorate. The get-go i is their concept of a complex cosmos in which at least two worlds - or more than - coexist, exist they side by side or one in a higher place the other. Those worlds interact with one another and in our own earth most events are believed to be the consequence of an influence from the other-world(s). The second one is the belief of the group in the ability for sure persons to have at will a direct controlled relationship with the other-world. This is done for very applied purposes : to cure the sick, to maintain a expert human relationship with the powers in the other-world, to restore an upset harmony, to reclaim a lost soul, to brand good hunting possible, to forecast the futurity, to cast spells, etc. Contact happens in 2 ways: spirit helpers, very oftentimes in animal course, come to the shaman and inhabit him/her when he/she calls on them ; the shaman may as well transport his/her soul to the other-world in order to meet the spirits there and obtain their assistance and protection. Shamans will do so through trance. A shaman thus has a near of import role every bit a mediator between the real earth and the globe of the spirits, also equally a social role.

Upper Paleolithic people were Man sapiens sapiens like us and therefore had a nervous organization identical to ours. Consequently, some of them must have known contradistinct states of consciousness in their various forms including hallucinations. This was part of a reality which they had to manage in their ain manner and according to their ain concepts. This is explored in more detail by Dr. Ilse Vickers in her department The Descent into the Cave in the Cave Art Psychology Archive.

Panel of the Black Horses discovered in 1985 by diver Henri Cosquer

This being said, nosotros know every bit a fact that they kept going into the deep caves for twenty thousand years at the very least in order to draw on the walls, non to live or take shelter there. Everywhere and at all times, the underground has been perceived as existence a supernatural world, the realm of the spirits or of the dead, a forbidding gate to the Beyond which people are frightened of and never cross. Going into the subterranean world was thus defying bequeathed fears, deliberately venturing into the kingdom of the supernatural powers in order to meet them. The analogy with shamanic mind travels is obvious, only their underground gamble went much across a metaphoric equivalent of the shaman's voyage : information technology made it real in a milieu where one could physically motility and in which spirits were literally at manus. When Upper Paleolithic people went into the deeper galleries, they must have been acutely aware that they were in the globe of the supernatural powers and they expected to see and detect them. Such a state of mind, no doubtfulness reinforced by the instruction they had received, was sure to facilitate the coming of visions that deep caves in any case tend to stir up (equally many spelunkers take testified). Deep caves could thus have a double part the aspects of which were indissolubly linked : to brand hallucinations easier; to arrive impact with the spirits through the walls.

Wall images are perfectly compatible with the perceptions people could have during their visions, whether one considers their themes, their techniques and their details. The animals, individualised by means of precise details, seem to float on the walls ; they are disconnected from reality, without any ground line, ofttimes without respect of the laws of gravity, in the absence of any framework or surroundings. Elementary geometric signs are always present and recall those seen in the various stages of trance. As to blended creatures and monsters (i.e. animals with corporal attributes pertaining to various species), we know that they belong to the world of shamanic visions. This does not hateful that they would take made their paintings and engravings under a land of trance. The visions could be drawn (much) afterwards.

Trying to get into touch on with the spirits believed to live inside the caves, on the other side of theveil that the walls constituted between their reality and ours, is a Paleolithic attitude of mind which has left numerous testimonies, peculiarly the very frequent utilize of natural reliefs. When one's mind is full of animal images, a hollow in the stone underlined by a shadow cast by i'due south torch or grease lamp will evoke a horse'due south back line or the hump of a bison. How then couldn't one believe that the spirit-animals constitute in the visions of trance - and that one had expected to find in the other-globe which the underground undoubtedly is - are not there on the wall, half emerging through the stone thanks to the magic of the moving light and set up to vanish into it again. In a few lines, they would be made wholly real and their power would and so become attainable.

Cracks and hollows, every bit well equally the ends oropenings of galleries, must accept played a slightly different withal comparable function. They were not the animals themselves merely the places whence they came. Those natural features provided a sort of opening into the depths of the rock where the spirits were believed to dwell. This would explain why nosotros find so many examples of animals drawn in function of those natural features (Le Roseau Clastres, Le Travers de Janoye, Chauvet, Le Chiliad Plafond at Rouffignac).

In addition to the drawings of animals and signs, the intention to go in touch with the powerful spirits in the subterranean world may also be glimpsed through three other categories of testimonies. Offset, the bone fragments and other remains (teeth, flints) stuck or deposited in the fissures of the walls. Finger tracings and indeterminate lines might stalk from the same logic. In their case, the aim was not to recreate a reality every bit with the animal images just to trail one'due south fingers and to leave their traces on the wall, wherever this was possible, in order to establish a direct contact with the powers underlying the wall. This might exist done by not-initiates who participated in the ritual in their own fashion and with their own means. Finally, hand stencils enabled them to become farther yet. When somebody put his or her mitt on to the wall and pigment was blown all over it, the hand would blend with the wall and take its new colour, be information technology red or black. Nether the power of the sacred paint, the manus would metaphorically vanish into the wall. Information technology would thus, concretely, link its possessor to the world of the spirits. This might enable the 'lay people', mayhap the sick, to do good directly from the forces of the globe across. Seen in that low-cal, the presence of hands belonging to very immature children, such as those in Gargas, stops being extraordinary (Clottes & Lewis-Williams 1998, 2001).

Stone Art Links

Source: https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/clottes/

Postar um comentário for "What Is Paleolithic Art Jean Clottes University of Alabama"